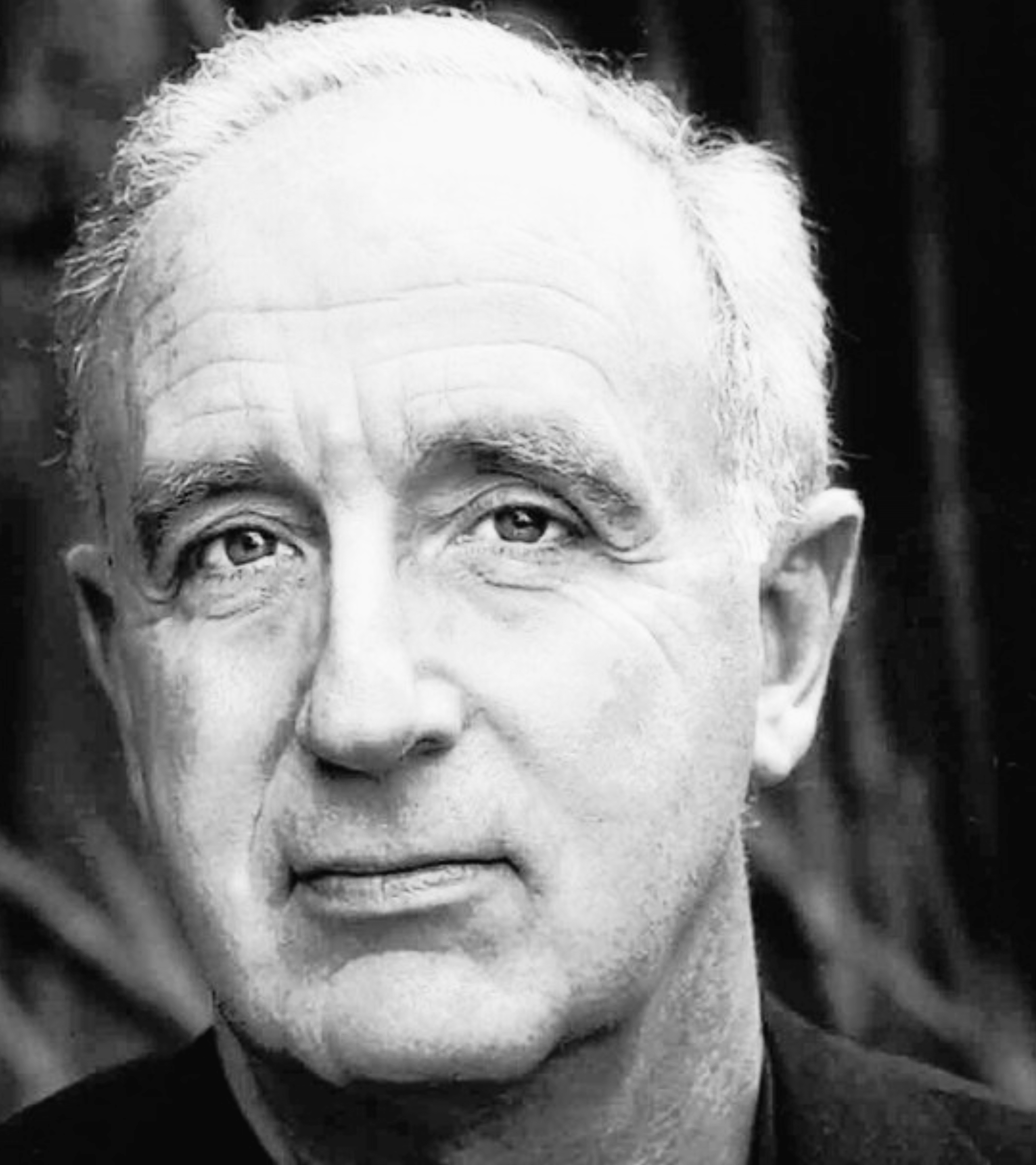

Get ready for an incredible conversation with the incomparable Steven Pressfield, whose novels and books on creativity have inspired countless creators. Our connection dates back a decade and has been instrumental in my journey to becoming a full-time writer and coach.

Steven is the author of the bestselling novels Gates of Fire, Tides of War, and The Legend Of Bagger Vance, which turned into a huge movie with Matt Damon, Will Smith, and Charlize Theron. He’s also the author of the classics on creativity, The War Of Art, Turning Pro, and Do The Work. These are my absolute favorites and must-read books if you’re creative, create any type of content, an entrepreneur, or simply someone with a dream in your heart.

He’s also just released The Daily Pressfield, which is 365 days (plus a bonus week) of motivation, inspiration, and encouragement. I received an advanced copy of this and it’s absolutely incredible!

This chat delves into the heart of creativity, ambition, and inspiration. But it really centers around resistance. Often seen as the most daunting hurdle in the creative process, Steven equips us with wisdom on how to overcome it.

Whether you’re an artist, author, entrepreneur, or 9-5’er, there’s something in this episode for everyone!

With love, 💕

Susie Xo

WHAT YOU WILL DISCOVER

How to beat resistance/procrastination

How resistance can be the most intense when the project is closest to our hearts

Steven’s own experiences with surrendering to the universe in order to make breakthroughs in his work

The power of finishing a project and how ambition plays a crucial role in an artist’s journey

The mysterious sources of creative inspiration and how to tap into it

The importance of embracing imperfection

How imperative it is to take risks and put ideas out into the world, even when they aren’t perfect

The challenges of maintaining focus in our fast-paced world filled with distractions

The necessity of staying true to our creative integrity

FEATURED ON THE Episode

Get my signature course Slay Your Year (Value: $997) for FREE if you leave a review of this podcast.

Podcast Transcript

Welcome to Let It Be Easy with Susie Moore.

Susie Moore:

Oh my. We have one of my favorite authors of all time on the podcast, Steven Pressfield. If you know Steven, you'll know how monumental this is that he and I are talking. I love him so much, and if you don't know him, then this might be the greatest gift you get this year, this conversation, Steven is the author of the bestselling novels, Gates of Fire and Tides of War, as well as the Legend of Bagger Vance, which turned into a huge movie with Matt Damon, Will Smith, Charlize Theron. He's author, also the author of the Classics on Creativity. These are my personal favorites, the War of Art, Turning Pro and Do the Work. These are must read books if you are creative, if you create any type of content, if you're an entrepreneur, if you're someone who has a dream in your heart. Steve has such an interesting story.

He was 52 when his first book was published, and now he has 20 books on the shelf. The most recent is The Daily Pressfield. I absolutely adore this book, read it every single morning, and let me just tell you that Steven Pressfield has made my life so much better. I understand myself so much more deeply, and I'm able to create and produce at a far more rapid pace than ever before because of his teachings. So my friends, I think you'll love this conversation. You'll fall in love with him just like I have. I give you Mr. Steven Pressfield. Steve Pressfield, is it really you?

Steven Pressfield:

It's really me. Is it really you? Susie Moore?

Susie Moore:

Oh, yes, it is. I have been waiting for this moment. I feel like the words that you've put on various pages in multiple books are tattooed in my brain and I repeat them like a parrot. I buy your books endlessly for friends. I just love your work, Steve.

Steven Pressfield:

Thank you. Well, thank you. It's great to be here with you. Let's, let's do our thing here.

Susie Moore:

Let's do our thing. You won't remember this, but I wanted to kick off by sharing with you how you and I first got connected 10 years ago.

Steven Pressfield:

Ah. Please tell me.

Susie Moore:

I emailed you and I found the email exchange last night. So it was Saturday, November 29th, right? So this is 2014. So nine years, coming on to nearly a decade ago. I messaged you saying the subject was, Hi Steve. And I said, Dear Steven, I'm sure a lot of people say this, but I really think I am your greatest fan. The War of Art and Turning Pro have spoken to my soul so deeply, and I refer to and quote them regularly. Your team even tweeted me this year after I quoted you in my Huffington Post article. Steve, I just turned pro. I quit my lucrative sales career to write, teach, and coach full-time. It's terrifying and exhilarating when you spoke of a shadow career and what it is a metaphor for, I've known deep down all along about mine. So thank you, Steve. That is all.

Steven Pressfield:

Well, that's great. Thanks, Susie. Yeah, great.

Susie Moore:

You wrote back

Steven Pressfield:

And here you are. I did. Wow. What a Guy.

Susie Moore:

Wrote back, you changed your subject line. You said, go for it, Susie. I felt like my life, my life was made and you said, Susie, I salute you. Good luck and Godspeed in your new professional life. I'm sure you'll do great, and if you don't, you can always blame me. That is all SP and I was like, that is just what I need. It's Steve, thank you for being you.

Steven Pressfield:

Well, I'm so relieved that everything worked out for you, Susie. You're not sending this note from underneath an overpass somewhere.

Susie Moore:

I can't tell you how you gave me exactly what I needed, and truly, this is why I speak about your work. So I mean, so at length with my communities, in my media pieces everywhere, and I'm not sure I'd be doing the work that I'm doing and look, I'll say successfully. Thank you very much. Without your encouragement and your wisdom and your even unknowing unknowingly being such a big mentor for me.

Steven Pressfield:

That's great. Well, thank you very much. Touches my arc. It's great.

Susie Moore:

Well, Steve, oh my gosh, I have to congratulate you on this masterpiece, The Daily Pressfield. Wow, where has this been all my life?

Steven Pressfield:

Ah, great. Yes, it's coming out in a couple of days. We're trying to figure out how, it's not on Amazon yet, but it's coming out in a couple of days.

Susie Moore:

I noticed that because I was looking for the official release date, et cetera, et cetera, but I was going through the daily press field and I was thinking, wow, you wrote about resistance so many years ago. It was like you put words to that universal thing that creatives suffer from, and we think that it's us and we hate our lives and ourselves and we berate ourselves. I mean you know it more than anyone. I wanted to just kick off by asking, is resistance still something that you have? Is it something that you has evolved or you think about differently now?

Steven Pressfield:

No. In my experiences, it never goes away and never gets any easier. And if anything, in a way it gets a little worse because it gets a little more nuanced diabolical it kind of knows you so well that it knows which little nuance buttons to push. The only, well, the good part of it is that over the years as you know, you start to have an experience of overcoming it, and so you can say to yourself, okay, I beat this in the past. I can beat it today, but it never gets any easier. I don't know why it should. It's like gravity. I mean, does gravity ever go away? No. Does the moon ever fall out of the sky? No. So it's always going to be there. I think, I mean, do you have that same feeling?

Susie Moore:

Yes, I absolutely experience resistance, but I can put words to it now. I say I'm experiencing resistance. I don't think I have some weird nuance problem and I have a special issue that no one has ever had in history, and I guess I'm not meant to do this work, throw my hands in the air and go to the pub. I mean, it could go that way without what I've learned from you and without just kind of knowing you say that it's this thing that affects creators universally, right? It touches. And you also say too that the bigger and more important the project to your heart, the greater the resistance.

Steven Pressfield:

Yeah. I mean, I've definitely found that absolutely true, but I even have to sort of remind myself of that. To this day, I'm just in the middle of a project right now. I'm at the very, very end actually, and I'm having a million self doubts, am I crazy? Have I just wasted the last few years? Is anybody going to be interested in this other than me? It's not The Daily Pressfield, it's another book. And I'm just telling myself that the bigger the resistance, the better the idea is. So that's what I'm telling myself. Sometimes I don't believe it, but that's what I'm telling you.

Susie Moore:

I'll tell you, I read a few great books by someone very well, and I know especially it really is that end part, right? It's like the...

Steven Pressfield:

Yeah, it's a killer.

Susie Moore:

Oh, it's such a killer and how human we can all feel when we, human and connected and more gentle on ourselves. We can feel when we come back to this truth. I mean, I reread your books often, especially when I need to be fired up or if I think, oh, why don't I, I'm like get on with it. Do the work. So Steve, you've had your first novel Public, well, your first piece of work published in your fifties, right? The Legend of Bagger Vance turned into a huge movie, Will Smith, Matt Damon. Charlize Theron, I mean big time. And I know that you said it was initially a novel that turned into a screenplay, and what I found fascinating about this is two parts. Number one, doing something for the first time in your fifties. I think that that's extremely encouraging for anyone. And then also the fact that it was what you wanted to write because it wasn't like, oh, this golf thing, I don't know. And the good old third party validation that you speak about too. It wasn't there, but could you just speak to that for a moment? I think that we never want to trust our ideas. We think, well, what's on the bestseller list? How do I imitate that? Et cetera, et cetera.

Steven Pressfield:

Yeah, I've been thinking about that a bunch lately because I really believe that when something is really coming from our deepest well inside us, it always surprises us, or at least it surprises me. I think of it sort of like, I'm a big believer in the muse and the goddess and it's to me. It's like the muse calls you forward and hands you an orders packet just like you were in the military and you open the envelope up and you look at it and you go, me? This must be for somebody else. Why is this happening, coming to me? I'm not an expert in this area. I don't know anything about it. I don't even believe it's commercial. But then as you get into, at least this is my experience, as you get into it, you begin to trust it. It takes a while, like nine months or something like that, and you start to think to yourself, well, maybe there is something to this.

But it seems to me if it doesn't surprise you, if the idea doesn't surprise you, there's something wrong. If it's too easy, if it's too much in what people expect from you, then maybe you should doubt it a little bit. So that book, the Legend of Bagger Vance, I just thought, this is the most uncommercial idea ever. I'm a complete idiot for doing this. I had to really go out on a limb and kind of leave a screenwriting career to do it, but I just was so seized by the idea that I just had to do it. So I just think in some crazy way, that's the way the universe works. It surprises you and it makes you have to trust it. It makes you have to surrender to it and in the face of your own self doubt.

Susie Moore:

And this takes great courage because a lot of people will also pile on your own self doubt. I mean, you say about how brain surgery is easier. Yeah, I mean, I love that. Oh my God, which one of my many highlighted pages is this one? I know it's very early on, but you say essentially you can go to school, you can go to school to study brain surgery. There's at least a path for that. What creatives do, it's like there's nothing and then there's something. Could you speak to that for a moment? I think creatives too. Any type of entrepreneur also, we think, oh, I should figure this out and it should just be a straight path. Because look at those three success stories or..

Steven Pressfield:

If you sort of compare any creative thing, music, writing or whatever it is to let's say brain surgery, this is one of my analogies I like to make. Brain surgery is a million times easier because there's already a structure, there's a path, a trail that's already been blazed. A million people have already done it, they've gone to medical school, they've gone to the specialists, they've been interns, they've been residents and so forth. So if you and I are starting out on this path to be a brain surgeon, we know that it can be done. And also there are mentors. We have teachers, there's an actual curriculum you take year one, year two, year three. And if you just keep going, you're going to get there. And you also have peers. You have your fellow students that when you start to freak out, you can go to them and say, Hey, man, are you freaking out too? And they say, yeah, yeah. I also don't understand organic chemistry or whatever it is. But if you're writing a book or you're following the music or you're doing any of those things, you're alone. You can't even talk to your spouse because it's boring. They may root ,cheer for you, but you can't say, here, read chapter one through six. They don't want to do that. And even if they did, they wouldn't know what to say. So you're just kind of alone on an iceberg. And the other thing is that although books have been written and albums have been recorded in the past, no one's ever done your book or your podcasting career or your entrepreneurial career and the problems that it presents. You can't find the answers in a book. You can't go to a teacher. You have to solve 'em on your own. And these are skills that they don't teach you in school. In fact, there's not even a name for those skills. So it's a lot harder to do this stuff. And my hat is off to anybody that can do it in any field, dance, music, you name it, filmmaking, whatever.

Susie Moore:

Me too. Especially after years of doing it now. And I think that what you're sharing right now, Steve gives people great relief, right? Because I think sometimes if we're suffering or if we feel isolated, we think that we're doing it wrong or we think that

Steven Pressfield:

That's true. Yeah.

Susie Moore:

Like you said, there's no right or wrong answer. Like you said in the chemistry book, you go page 120, it's like, I don't know if your character's going to die. I don't know if you should interview that person. I don't know if you should pitch that, it's up to you.

Steven Pressfield:

Yeah, absolutely. And the other thing is, just as an example of what we're talking about, let's say as a writer, you get to page 61 of a novel, you're writing and you read it over for the first time. You look at it and you say, this is dog shit. This is not working. This is terrible. And somehow you have to find the resources within yourself to say, okay, what's wrong with it? How can I and not be discouraged? The thing about it, first of all, like I say, nobody teaches you how to do that. You got to figure it out on your own. Where are you going to dig deep and find the resources? But the other thing, Susie, is that let's say you succeed, you conquer that fear, you start again, you get it going. Nobody knows. Nobody rewards you. It's not like you're on a football team or a basketball team and you hit a three pointer from 40 feet and everybody cheers. It's like you've just done something great, but nobody knows. You can't share it with anybody. You can't turn to your spouse and say, let me tell you how I just recovered from this. They're bored to death. They don't care. So the whole thing about the artist's life is internal self validation. Self reinforcement, giving yourself a pat on the back, driving yourself forward when you have to, letting yourself take a break, when you need to take a break, but it's all inside your own head. That's why it's so difficult and why nobody's really prepared for it. There's no way to do it until you actually do it.

Susie Moore:

Exactly. And like you said, I agree, it doesn't get easier. Your projects just, I think probably get maybe a little bit, maybe a bit better funded or you just have a bit more experience in certain areas. But the new dream brings a whole new, I mean, every time. I think really, if you're staying in the game, and like you said, no one really does want to hear it, they don't understand it. I used to say that marriage is the ultimate crash course in personal development. I've been married very happily, but I'm like, it's not. It's going out on your own. That is like, I have to coach myself daily. Come on, come on back, okay, this isn't the end of my life. We can...

Steven Pressfield:

Yeah, so true.

Susie Moore:

Yeah. But you've given me such context to even understand that that is, I mean, and to also share that with others because the ego will have us believe that we are really alone and that we are not.

Steven Pressfield:

It is encouraging to know that other people suffer with this same stuff too. Every time I read about Philip Roth or Tony Morrison or any great writer or any musician or anything that they've had racked with self-doubt and all that sort of stuff, it always encourages me. I figure, well, I'm not the only one that's going through this stuff. And of course, it's true for everybody. Every time you read somebody's autobiography, Keith Richards or anybody like that, you go, wow, man, the guy was really suffering. It seems so easy watching him, but he had to go through a lot of stuff.

Susie Moore:

Because that's what we see. We only see the finished end result, which is always successful if we're seeing it, right. You don't see all the crap in the waste paper basket. We don't see all the

Steven Pressfield:

Yeah, exactly.

Susie Moore:

We see the finished success story, and that can be yes, inspiring but also intimidating. And we're like, I'm just here with my old laptop just trying to put 500 words together, man. I mean, there are a couple of things that come to mind as you speak. One thing that it always makes me cry whenever I read that particular passage, I think it's in the War of Art of all of your books, you say when someone completes something, you applaud them like Atticas Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird, and you're saying, I see you, I applaud you. And that just moves me so much because I feel like it really is that unseen piece that gets no recognition,

Steven Pressfield:

Which is why I think it's so important for all of us to recognize our peers and those who are following behind us and those who are ahead of us. I just was having breakfast with a friend of mine the other day, and he kinda got, we were talking about a bunch of stuff, and then he got sort of a little embarrassed, and he kind of said, I'm a little superstitious about telling you this. And he confessed that he had just finished a screenplay and he's in the movie business, but not as a writer. And I just immediately reached across the table and shook his hand because it doesn't really matter, good, bad or whatever, and it might be really great, but even if it isn't, God bless him for doing it and for finishing it. And he was kind of afraid to tell me because it was like, would he be jinxing it if he told even one person? So I was very flattered that he told me, and all I wanted to do was to validate him and say, this is fantastic. God bless you. Keep going.

Susie Moore:

And he probably needed that more than he even showed you. I think this is a thing that we need. We don't even know we need it sometimes. Ideally we can give it to ourselves, but even that, we can use that up sometimes. So imagine everybody, Steve is applauding you. Steve is shaking your hand when complete, right, the end.

Steven Pressfield:

But it's true. I applaud everybody that can get there. That was my demon, biggest one forever, finishing something, getting to the end and not choking and not blowing it up. So anybody that gets to the end. That's fantastic.

Susie Moore:

Yeah. Could you speak to that a little bit for anyone who doesn't know your story or the various jobs you had, the winding paths that you've taken to get to the work that you do now, specifically in your fifties getting really serious.

Steven Pressfield:

We'd have to be here for eight hours.

Susie Moore:

The summary, the real summary

Steven Pressfield:

One, just one story on the subject of what we're talking about here. I tried to write a novel when I was like 22 and had no business doing it. I had no clue what it was going to take. And after about two years of stuff being supported by my young wife that loved me, blah, blah, blah, and I had no idea what resistance was, had never thought of it, heard of it, no clue. And it just totally blindsided me. At the end, I was like this far from the end, and I just choked, blew up the marriage, blew up, blah, blah, blah, everything, and wound up kind of on the road working jobs in the oil fields and driving trucks and things like that. And finally, I don't know, maybe seven years later, I finally, I saved up some money. I moved to a place that was affordable. I rented a little house and I worked for two years nonstop. And I finally finished something and I write about this in the War of Art, and this was back in the days of typewriters when it was, nobody knows what even carbon paper is, but I had a stack of papers. That was the thing. It wasn't a digital file. And when I finally finished that thing, again, it's like we were just talking about Susie. Nobody knew I'm totally alone in this little house. Nobody knows I'm even there. Nobody's going to pat me on the back, nobody's going to give me any kudos. And the book, of course, never sold, never came close to finding a publisher. In fact, it would be like another 15 or 20 years before I even made the first penny off of anything. But in that moment, I finished it. So that's why I'm so, and I could feel like my DNA were changing in that moment, and that's why I applaud anybody that can finish it. And I'll say one thing for whatever this is worth, having finished it one time, I've never had trouble finishing anything ever again. So I say that to anybody that's out there trying to get over that hump. If you can just get over that last scary part, you'll never have trouble again after that.

Susie Moore:

It's like you're only a beginner once. You only have to figure it out and then you know, can repeat it. It's still going to be hard, but you can repeat. Yeah,

Steven Pressfield:

It's amazing. I don't know how it really works. It's something visceral. It's something on some other level other than the brain.

Susie Moore:

You say also, and I love this, that when there's resistance, the resistance comes second. It's not like resistance just lives and swells around. It's like there has to be a dream first, right? There has to be a vision first, an idea. Could you speak to that for a moment? Because I think that we so quickly, we're so quick to erase or forget, or not even give a second of attention to the dream, but just dream resistant. Oh, idea. Forget it.

Steven Pressfield:

Yeah. This is kind of an important point for anybody that's struggling and that resistance comes second. The dream comes first, and then the analogy that I use for this is if you imagine a tree in the middle of a sunny meadow, and as soon as the tree appears, a shadow appears instantly. So the tree is the dream and the shadow is resistance. So again, like we were saying before, the bigger the resistance, the more important a project is to you. When we feel that resistance, that's the shadow that we see of the tree. But there wouldn't be a shadow if there wasn't a tree. And the bigger the shadow, the bigger the tree. So the more resistance we feel to something, the more afraid we are of it, the more we tend to procrastinate, the more easily we are distracted. The more even we're feeling symptoms like depression and all that sort of stuff, the more we feel that that's a good sign. That's the evidence of resistance. That's the shadow that tells us that there's a tree there. And so we know whatever that dream is, that object, you want to be a podcaster, you want to, whatever it is, you can tell by the scale of the resistance that that's what you got to do, that you're onto something. It's not nothing. If you had some shitty little dream, you'd just have a little tiny shadow. You wouldn't worry about it. But when you got a big one, you got a big dream. And that's good.

Susie Moore:

Oh my God. I mean, you say too, and I want to get it right, I wrote it down here. Oh, I love this. I quote this a lot, but I want to get the exact sentence in your words you say, which speaks to what you're just saying, "To feel ambition and act on it is to embrace the unique calling of our souls"

Steven Pressfield:

Which I think is absolutely true.

Susie Moore:

Which is that tree.

Steven Pressfield:

Right? I mean, when I was, by the way, let me say something, Susie, I think thank you for your preparation on this. You're really making this conversation go in interesting places, I think. But

Susie Moore:

Oh, I've waited 10 years for this, Steve, In three days. But

Steven Pressfield:

What you just said, I kind of came of age during the hippie era, during the counterculture era, and in that time, the word ambition was a dirty word, because if you were ambitious, it was as if you were saying, well, I'm better than my brothers and sisters, and I'm going to leave them in the dust, right? I'm going to compete with them and defeat them somehow. And there's something to be said for that. But in terms of art or of a creative calling, ambition is the heart and soul of it. It really is a new life that's growing inside you like a baby and a pregnant woman, and that's the call that's coming from that new life to you equates to ambition. So it's totally positive and it's totally sacred, and it's a calling that you should not. It took me a long time to sort of get over that feeling that this was a bad thing, to feel like I wanted to do something. And once that was a big breakthrough for me to kind of say, it's okay to be ambitious. It's okay to want to do something great. In fact, it's a real blessing to feel that calling.

Susie Moore:

Oh my gosh, Steve, I can't tell you. When I read those words from you, how I highlighted them to photo share them. Oh my gosh. I'm like, yes. I remember thinking when I had my very well-paid sales career, I'm like, why do I have this dream? It's so annoying. Why can't I just want what I've got? It would be so much easier. And look, I used to go out with all my clients drink too much. The resistance was just showing up and like, well, fuck it. This, you say, and I believe it's the war of art. If we overcame resistance, we'd have empty hospitals, we'd have empty. We create this drama almost like sometimes theatrics, you talk about the girl who brings home a boyfriend from prison or something instead of doing her creative work because she's like, this is how I can get attention. It's like the cheetah. I mean, I see it. I know it. Could you speak to that for a moment? Sometimes I think we're like, oh, there's something wrong with us. I keep distracting myself.

Steven Pressfield:

I just think that, how am I going to phrase this? We all have, I think of it sometimes as an underground river that's flowing inside us. That's our calling, our vocation, our creative thing, whatever it is. And we sometimes think, oh, it's okay if I don't do this, if I blow this off, if I have other things that I follow, some shadow career or something, that's not the real thing. And we think that there won't be any consequences, but there will because that river keeps flowing and it's like something that wants to be born and we're not letting it be born. And so what happens is it becomes malignant in one way or another. It shows up in other areas of our life and in depression, in self-abuse or abuse of others, or all

Susie Moore:

Of overspending, everything, yet all the vices.

Steven Pressfield:

I mean, I think that a lot of the vices of the modern world, alienation, loneliness, addiction, if each one of us could face our calling and do what it is that we were meant to do, all that stuff would go away. Mental hospitals would empty overnight. Addictions would go away overnight. I think maybe I'm oversimplifying things, but I do think there's, when we don't let that thing be born, it goes into malignant channels and it turns against us.

Susie Moore:

I agree. I've experienced it. And I think that we do what we can to soothe ourselves. We do what we can to still make our life exciting somehow in other ways, whereas sitting down to write, it doesn't feel like that's the most exciting thing on earth. But I tell you, the adrenaline is high. When you are connected to something that you don't know, it's invisible. But it's like when you kind of reference Bob Dylan, or even I think John Lennon in one of the books, you're like, creatives are humble. There is something, there is a humility there. Not like I'm the best forever. Or if there's someone like that, they don't stick around very long. You notice, we realize that we're tuning into how you, I know we talk about the muse. Is that what you always refer to? Is there anything else in your own mind that you think that you are connecting with when you are creating?

Steven Pressfield:

That's really it. I mean, sort of the long story of this thing, if you can stand this, Susie, I think I wrote about this somewhere, is when I first saved up money and moved into this little town and this little house to write a book. And I had two years worth of money, which at that time was 2,700 bucks. And I had a friend who was a writer who lived down the street. His name was Paul Rinky, lived in a camper, and I used to have coffee with him every morning. I do. And I had never thought about the idea of the muse or the muses, the goddesses, the Greek goddesses that inspire artists. And he sort of introduced me to that concept. And he typed out from Homer's Odyssey, the invocation of the Muse, which starts the thing. He typed it out, he gave it to me on a sheet of paper, which I still have right over there.

It's crumbling. But the idea that, I guess it's a question that it comes down to the question of where do ideas come from? And the reason Bob Dylan, I was just reading this about him the other day, and he said he doesn't even remember writing the songs that he wrote. In other words, they came to him from somewhere, but where did they come from? And that's this mysterious question that we don't know the answer to. Rick Rubin calls it Source with a capital S. Yes, I call it the Muse. I like that kind of Greek mythology thing. But it's coming. And like Elizabeth Gilbert, she'll talk about actually speaking to the corner of the room and just saying, Hey, give me some help here. I'm stuck. And she's talking to that mysterious force, whatever it is. And so I have to thank my friend Paul, for just turning me on to that idea, which has been central to my whole concept of what I'm doing forever

Susie Moore:

Since, and this is where you say, this is where you say, put your ass where your heart wants to be. So actually sit down or go in front of the canvas, go to the studio, wherever it is that you create. And I love speaking of Paul Rink, how you end. I believe it's, that ends with the story where you say, I went to my friend Paul Ring's house, and I told him I just completed something. And he said, yeah, start another one. And I'm like, oh, yes, of course. That's going to be how it ends.

Steven Pressfield:

That's another great gift that he gave me when I had finished this book. And I went down and I told him, it was like he didn't congratulate me. He said, good luck, good work. He said, start the other one today. The next one today. Wow. And it's so true. I'm a complete believer in that of not stopping to wait for the world to applaud you, but keep going on the next one. And it'll all happen down the road a little bit.

Susie Moore:

Yeah. I mean, I even look at people who are really prolific in this day and age, someone like Taylor Swift, who's pretty young, and she's got 10 albums. She just did a big tour. It's sold out to, it's still going actually three and a half hours of songs, and she's using a tiny percentage of her music, her library. And I think, is she such a genius? I know you say talent is bullshit, love that. I mean, is she such a genius or is she just connected and overcoming resistance? How do you think about something like that?

Steven Pressfield:

I mean, I can't don't know her, so I can't really speak to it, but she must be just one of those really lucky people that has the pipeline open to the muse, and the muse is just feeding her stuff, and she's just taking dictation and putting it down, and God bless her. The rest of us have to work awful hard. Maybe it comes a little easier to her than the rest of us.

Susie Moore:

Yeah. I listened to, there was an interview called, you might find this interesting, the New York Times do this. It's called Anatomy of a Song or Anatomy of a Piece of Art.

Steven Pressfield:

Oh, I don't even know about that.

Susie Moore:

Yeah. But they speak to an artist and they ask, how did you come up with this? How did you create this? And she said something like, when idea like a rainbow, you just got to catch it immediately and just get everything you can out of it. It moves quickly.

Steven Pressfield:

Oh, that's great.

Susie Moore:

You find the..

Steven Pressfield:

Yeah, I heard a story that Roseanne Cash said this, and she says, an artist or a musician has to carry a catcher's mitt because when the ideas flow through, you got to grab 'em before somebody else does. I think it's somebody like Taylor Swift. It's like we're all getting ideas all the time, but most of us don't even know it. Or the ideas come through and we dismiss them. We say, oh, that's bullshit. That's stupid. But someone like Taylor Swift or Roseanne Cash, they've got their radio dial tuned in, and when that idea comes in, they grab it, they get out their recorder, and they write it down and they jump on it right away.

Susie Moore:

I love that

Steven Pressfield:

If we could all do that, we'd be a lot better.

Susie Moore:

So I've been doing my podcast now for, it'll be two years in March next year. And I do it every single day, Steve. Wow. And I haven't missed a single day. It's like five minutes every single day, an episode that drops, and on Sundays interviews like this button, which I'm loving so much. And look, some days I'm like, gosh, am I going to record today? I've got my ideas right? I'm like, but every single time I get an idea, I just jot it down notes in my phone, and I sit down. And even if I don't think this is completely perfect, I'm like, you know what? It's good enough. And I give myself that permission. I've noticed that that's rare people.

Steven Pressfield:

It is rare. That's great. It's a great skill to have. There's another skill. They don't teach you, Susie. Nobody tells you that. But sometimes even those sort of half-assed ideas turn out to be good once you start to do them.

Susie Moore:

Yes. And better. A half-ass idea that's out there than a great idea that's buried. I think I'm like, maybe that wasn't my best one, but it's still something. It's still inspiration for someone that day. It could be the right message. So do you think that that's also part of it? Do you think that we have to be absolute masters of our craft and be perfect? Or do you think good enough can be, in fact, fair.

Steven Pressfield:

Enough? I'll sort of take both sides on that one. On the one hand, you certainly don't want to put anything out there that's not as good as you can do it. Yes. On the other hand, sometimes, like Seth Godin talks about shipping something like when Steve Jobs invented the iPhone, maybe it wasn't perfect, but at some point he said, we got to get this son of a gun out there. I'm definitely a believer in that. When the moment comes, don't be a perfectionist. Get it out there. And I say that because I had so much trouble the first time, that first book that I couldn't finish, I would noodle with it and mess, and then I just chickened out. I just chickened out. I didn't have the guts. I didn't know what resistance was. But that over perfectionism is resistance. And sometimes it's great to just get it out there. I'll tell you one story that's in another book. I had an agent when I was first starting out and I was working on a book, it never sold, but he really believed in me and he said, how close are you? And I said, I'm close. I'm close. And he said, close is good enough. Give it to me. And there was a lot to that. You can always revise it a little bit, but don't hang onto it until the moment has passed.

Susie Moore:

I agree. I also think that just speed of implementation, when we can act quickly, we are blessed with more and more ideas. I feel like as ideas are gifts, and if we get them out there, if they're stacking up, we can't receive new ones. It's like get it out. Get it out. That works in business from just a commercial perspective. But then I think creatively better to just be like, and I'm getting better each time, even if I'm learning as I go, which we all are, aren't we learning as we go? Who's the finished product? And then a friend of mine, he Ghost writes, or Co-writes now it is actually called Co-writing a lot of celebrity books. He's had six or seven big bestselling books. And he said, the books are never finished. He's like, you have to take them out of my hands, my claw. He's like, literally, the book is never finished. You always want to tinker with it. I'm like, good enough. I think there's a relief in that too, and maybe even more creativity.

Steven Pressfield:

It's a little bit, people sometimes say, you got to spend money to make money. You got to keep it flowing. You got to say, you get the ideas out there and then there's room for more to come in.

Susie Moore:

So I think my little flavor with this sometimes, because again, just in my community, it's called Self-Coaching Society, we just did a whole call on do the work. I'm like, I've got the book we are doing, do the, I'm like, we're waiting for you to do the work. And I think my little touch is, you know what? We don't have to take it so seriously. I mean ourselves so seriously. We can have fun with this. That's true. I mean, of course. And I think that, well, for me, I feel that allows more creativity in, I'm just less rigid with myself.

Steven Pressfield:

I do think when we're hanging onto it too tight and we're taking ourselves too seriously, that's another form of resistance. Stopping the thing getting done. If resistance loves it, when we're such perfectionist that we got to rewrite the last thing, and I'm with you, let it flow and get it out there.

Susie Moore:

Yeah. Hey, Steve. Okay. One thing that you say, which I absolutely love, haha, and I would love Haha to chat to you about this right now, is you speak about the writer writes the amateur tweets, and actually on day four of, oh, the daily press field, which everyone absolutely must have or their year is going to be terrible, you say, no, it's called No Distractions. And this is 365 days. You can start any day, but there's a snippet from Steve and then a bit of an update that he provides under each one. So it's Chef's Kiss. It's

Steven Pressfield:

Really sort of, if I can interrupt, it's sort of like what we're doing right now in this conversation. So he's like, you're saying, oh, I remember this, and would you please elaborate on that? So that's really sort of what the Daily press field is. It's kind of a comment at the start and then an elaboration on it. If you'll forgive me for

Susie Moore:

I absolutely love it. Can I just say something else randomly actually completely randomly. I also love to read The Daily Stoic, and I know that the Daily Pressfield is dedicated to Ryan Holiday. Amazing. But would you believe today, the day we're doing this interview, November seven, November seven is how to be powerful. You are referenced here. Oh, really? Steven Pressfield. I didn't know that on this day. I'm like, this is synchronicity at, I read it and I'm like, he speaks about you. I'm speaking about Alexander the great virtues of war, your reference to this and am like, oh my God, I'm interviewing Steven Pressfield today. I was like, the universe is amazing. I rest my case. Wow.

Steven Pressfield:

I got to open my copy and see what it is.

Susie Moore:

I know. But a daily Pressfield my also new daily, but you say on day four, no distractions. It goes without saying. I've turned off all external sources of distraction. No phone, no email, no Instagram, no Facebook. I'm on an ice flow in the Antarctic. I'm circling alone at 70,000 feet. I'm on the moon. Barring a nuclear attack or a family emergency, I will not, while I'm working on my attention to anything that's not happening inside my own demented skull. And then you say with your update, I've said for years, if you want to become an instant billionaire, invent something that makes it easy for people to succumb to the voice of resistance in their heads. Well, someone did invent it. It's called the web. It's called social media. It's called Going Down the Rabbit Hole of Distraction and Click Bait. I think we know this on some level, but I mean, because not really on social media.

Steven Pressfield:

Oddly enough, I just did a little post on that exact chapter. It's on Instagram right now. But

Susie Moore:

I mean, you're not active. You're not DMing people. You are not engaging. You're

Steven Pressfield:

Only in a very limited time. But certainly once I sit down to work, I have to lock the door and just focus on only that. I mean, it's like you right now. I mean, you're completely focused on what you're doing and the preparation before and the post-production afterwards, nobody's allowed in. You got it. And I think a lot of it, Susie, is about depth of work. The epidemic of modern times is that everything is so superficial. So on the surface, our attention span is like 4.6 seconds. But yet, when anything great is made a movie, an album, whatever it is, somebody sat there and beat their brains out month after month after month, a Martin Scorsese movie. I mean, the depth of what they've worked through to get to that is just amazing. But nobody wants to do it because we all have, our attention spans are so short these days. But if you can do that, then you're a mile ahead of everybody else,

Susie Moore:

Number one. I completely agree. And I think why it's so hard for anyone just to put their phone in a drawer for a couple of hours. I mean, you don't even need to go to a retreat in the Himalayas for six months. It's as simple as, or even just deleting a couple of apps for a while. I mean, these things are available to us. What would you say to someone, because this question does come up sometimes, who says, social media is okay, we sell on social media. So if you have a book, you're all over it. You're doing interviews, IG lives, you're toking about it. You are out there. Do you consider selling your art completely separate from creating art, or do you see it as one?

Steven Pressfield:

That's a great question, Suzie. Like when I first started in this racket, when my first couple of books came out, it was like the nineties, and it was an entirely different world where this is going to get long and boring. So bear with me.

Susie Moore:

I'm never bored.

Steven Pressfield:

In those days, there were newspapers. People read newspapers. Nobody, even the young generation doesn't even know what a newspaper is today. They don't get news there. And each newspaper had a book review section, the Boston Globe, the Atlanta Journal constitution, the New York Times, the Dallas Morning Herald, blah, blah, blah. All these books had book review sections, and people actually read them so that if you had a book coming out, it would get reviewed for me. When Gates of Fire came out in 98 or something, it got two reviews in the New York Times. It got a Sunday review and a weekday review. And so the bottom line for this is the writer, the author didn't actually have to go out on the road and sell their own shit. There was a mechanism in place where people could find out about it, but then all that went away. Newspapers, there's no real newspapers left. There's certainly no book review sections except the New York Times and the LA Times maybe, and maybe one or two somewhere else. So if you write a book, if you write a book, it's not going to be noted anywhere. When this book of mine, A Man at Arms came out about a year and a half ago, and I remember the publisher asked me and my partner, Diana, to, we put together 150 gift packs, and we sent them out to book reviewers. And you know how many book reviews we got? None. And

Susie Moore:

You, Steven Pressfield,

Steven Pressfield:

People are bored to death with me there. But in any event, so nowadays, it's a long way of answering your question. You got to get out there. If you look at, like Arnold Schwarzenegger has a book out now, whatever it's called, be Useful, I think it's called. And the guy is everywhere. He's on Ryan Holiday's podcast. He's on, he's everywhere. And if you talk to him, he'd say, this is what you got to do. You got to sell. So I hate it. Well, let's say it's not the literary vision that I used to have of what I wanted to do, but it's absolutely necessary. And Ryan Holiday's a big believer in this too. He says, well, the way I look at it is I have characters in my books, the novels anyway, that are real people to me, and they can't stand up for themselves.

I've got to stand up for them. I've got to give them their moment in the sun if I can. So yeah, it's part of the same deal. I figure maybe 40% of your time of the course of a book is really about, and I'm sure this is true of movies, and if Matt Damon has a new movie, the Guy's Everywhere for three months, he has to be, it's a shame that you have to do that, because it's better if a third person talks about you and says that when you're having to say yourself, Hey, read this. It's good. It's embarrassing, but you have to do it otherwise you're dead.

Susie Moore:

It's very honest. I feel as if some people think I love to create, I love to write, or I love to paint, whatever it is, and they're like being in front of people or talking about it, it absolutely makes them, they'd rather lose an arm or lose a leg. Yeah, that's true. And so I think, wow, this is a skill to learn then, because in my opinion, there's no getting around it. Yeah.

Steven Pressfield:

The other thing, I think it's like so many artists are introverts, right? That's kind of why they're artists, right? They wouldn't be good if they weren't. And so it's really hard for them, including me, to get out and flog your own stuff. But you have to do it. In fact, I would say you just have to have a thick skin. You have to enjoy it, turn it, make it fun, and somehow help out the characters that are in your book.

Susie Moore:

Yes, when it comes to success, because everyone defines it a little bit differently, but I know that there are some people, and they'll even admit it to a point, they'll say, I want to have a book to hit a bestseller list so that I can start charging more for my keynote speaking, and I'm even going to do bulk buys. I'm going to play the game completely, because that is my goal. The winning is more important than the writing. The list is more important than the art. What do you say in situations like that? What's your take? I'm so curious.

Steven Pressfield:

People do right for different reasons, and I can't knock anybody that wants to do that. That's human nature. But it's certainly not for me. That's not why I'm in this business. My whole belief is, to me, that sort of way of working comes completely out of the ego. It's about the ego. It's about me. It's let me be in the spotlight. Let me puff up myself, whatever. Whereas my feeling about what I do for a living is I'm trying to get away from the ego. I'm trying to let the ego go away and get on a higher level and communicate on a soul to soul level if I can. And I hope that the War of Art did that. I think it did. I think it got into people's hearts and other books of mine, I hope have done that. But yeah, I don't knock anybody that does what you just said, Susie, but that's certainly not the way I look at it. Not at all.

Susie Moore:

I'm with you. And I also feel as if sometimes, I mean, we see this on so many different occasions, like the person who, and you also say, okay, I've got you. I've got you endlessly quote Steve, you say to go into the arts, apart from love, besides any reason other than love is prostitution. Steve Pressfield another one right there. There's plenty more where that came from, but I feel like sometimes you can find, say an unknown or a new author, and then you find out this new author, actually it's actually her sixth book, and then someone discovers it or something happens and it's not out there on the circuit with her marketing team, and How can I play this? It's just open-hearted offering, showing up without applause, external applause.

Steven Pressfield:

Yeah. God bless anybody that does that. And it takes tremendous love for the material. And it's like you were saying before, I sold my first book when I was 52. And so people sometimes ask me, how did you keep going all those years? And in a way, it was a good thing for me because I had to ask myself, why are you doing this? Your family thinks you're crazy. Everybody else thinks you're crazy. You're not making any money. You're not getting any recognition. Why are you doing it? And I had to answer the question, and it was that I'm in it for the love of the game, just like a baseball player loves the, because there's no other reason in my mind to do it. You hope you can get paid, but the bottom line is that you really don't have any choice. At least that's in my situation. So that was a grounding for me that that's why I'm in this. I'm in it just for the love of the game because I can't do anything else.

Susie Moore:

When I sent that note to you nine years ago, I remember thinking, I've got no choice. I mean, I didn't even want it resign. And I was like, everything's changing. I don't even want this dream, but you can't ignore it. I knew that. I just knew on some level that if I ignored it, I'd end up sick. Something would just happen. Do you ever

Steven Pressfield:

Look back, Susie, and do you have any regrets at all?

Susie Moore:

I'm so proud of Michael the best. I don't even feel like it was a decision. I can say best decision, but when something just happens and you're just, it's like, I thank you, Steve. One conversation that me and my friends have, oh my gosh, I wish that this hour could last forever. Don't worry, I won't keep you forever. But one question that comes up with my friends and I is at a certain point too, if you've had some success, it is easy to sell out a little bit, right? Maybe I'm being a bit reductive here, but you do something and then someone's like, okay, do the version of that for people who do this or say, write a self-help book about getting up in the morning. And then someone's like, well do it for real estate agents and now do it for, because it's selling. Do you just always stay in your integrity? Is it always so clear? Sometimes you think it's okay to do it for the money? Do you think you can always course correct? What's your opinion on doing something for

Steven Pressfield:

The job? I'm definitely a believer in not shelling out like that if you can. Actually, good friends of mine have said that exact thing to me, people that I respect on other levels, and I don't want to say to them like, man, I can't do that. But that's how I feel. I mean, I've tried to sell out at various times, and it's like, nobody wants to pay me, but they'll say,

Susie Moore:

The Vos is protecting

Steven Pressfield:

You. We'll let you sell out, but here's like a thousand dollars. I go, what? I'm going to sell out a little more than that.

In the end, I think the reader or the moviegoer can tell right away that you're selling out. So I try not to, again, it's what I said before, that the newest, your new work should always surprise you, and it should always be something that is not cashing in on what you did before. It should be a little different. When Bob Dylan went electric, he was not cashing in. Everybody wanted him. Oh, let's have some more folk songs. And they hated him. I don't know if you, do you remember that? It's way before your time. I know. Susie, do you remember the thing about Bob Dylan going electric? You don't, huh? No. Well, he started out and he was a folk singer, and he had the harmonica around the, and at some point, I think this was with the band, he went electric. He had electric guitars, and he sort of started to shade over into rock and roll, and people hated it. I mean, it was in England that he did it, and they were virtually throwing cabbages at him on the stage. They thought, oh, he sold out. The guys a total failure. He is a sell out. He's a traitor. And people do hate you when you sort of break the mold a little. But God bless him, he stuck with it, and he's continued to do it. He always is changing. You never can tell what he's going to do next. And God bless him for doing that.

Susie Moore:

Something similar is true for David Bowie. Yeah. He was speaking about, yeah, there's

Steven Pressfield:

Another guy that was always reinventing himself. Yeah.

Susie Moore:

And someone said to him, do another song like Starman, and he's like, fuck this. I'm moving to Berlin. Yeah.

Steven Pressfield:

And

Susie Moore:

He just moved to Berlin and had two years of painting. And then he came out and people feel like even not to keep referencing Taylor Swift, but she moved from country. People feel like, don't betray us. Stay with us. And then it's like, oh, the expansion. And when you say, when it scares you, it's like, oh, it's showing you come this way. And it's almost like these endless resolves we can tap into if we allow it,

Steven Pressfield:

If, yeah. Another one is Linda Ronstadt, where she did Pirates of Penance. She was a rock and roll singer. Then she started connecting with her Mexican heritage, and she did that song Canciones, or that album of her father's songs. And she just kept reinventing it. And people gave her shit as it went along too. It's like, why are you doing this? But then she was so great at it, everybody goes, wow, this girl can do anything.

Susie Moore:

Oh my God. So if someone, Steve is on the brink, right? Just say that they're experimenting, they're putting work out there. Maybe they're new, maybe they're established and they're pivoting or they're expanding and they haven't got that breakthrough yet. They haven't got the three PV, as you call it, third party validation, and they think, should I give up? Is this a failure? Do I need a break or do I need to keep going? What would Steve say?

Steven Pressfield:

I would sort of go back to the concept of resistance and ask myself or anybody that was in this self-doubt or whatever it is that's plaguing you at the moment, that's making you think you want to quit. Is this resistance? Is this this phony baloney? Is this as the evil force of resistance trying to stop you? And if it is, then that's a good sign and it tells you you got to push through this, that you're onto something. So I would say there's almost never a moment when you can say, okay, I'm going to give up. I would always push through to the end, and it's better to finish something and have it completely fizzle than to stop, finish it, and move on to the next thing. That's what I would say.

Susie Moore:

What do I know? Just Paul Rink told you. Yeah. I would love to end this fantastic conversation with one of my favorites, actually from the daily press field, day 362. Do you remember what that is?

Steven Pressfield:

I do know what it's about, the practice, right?

Susie Moore:

It's Are you a born writer?

Steven Pressfield:

Oh.

Susie Moore:

See, there are so much you can't even remember. Seriously, I've got so many point notes here, but what can you do? I hope you'll come back, but this is what you say, Steve, are you a born writer? Will you put on earth to be a painter, a scientist, an apostle of peace? In the end, the question can only be answered by action. Do it or don't do it. It may help to think of it this way. If you are meant to cure cancer or write a symphony or crack cold fusion and you don't do it, you not only hurt yourself, even destroy yourself. You hurt your children, you hurt me, you hurt the planet, you shame the angels who watch over you and you spite the Almighty who created you and only you with your unique gifts for the sole purpose, nudging the human race one millimeter farther along its path back to God. Creative work is not a selfish act or a bid for attention on the part of the actor. It's a gift to the world and every being in it. Don't cheat us of your contribution. Give us what you've got, Steve. Oh my God, I love you. I love your work. I love your words. Where do people go to follow you? Get the book. Tell us the things.

Steven Pressfield:

Actually, right now, I'm not sure when this podcast is going to drop, as they say, but the Daily Press field comes out at the end of this week, which I guess is November 10th. It won't be up on Amazon right away, but you can go to my website, steven pressfield.com, and we have a special gift edition, and we have a regular signed edition. That's the place where you can get it right now. It should be up on Amazon really soon. And there you have it. It's,

Susie Moore:

And the Companion Journal. It's

Steven Pressfield:

A pen journal in there and a bunch of other goodies too. And it's illustrated by a wonderful illustrator, Vic Juhas, who did 52 1 a week. Great illustrations in there. They're better than the book, better than they all.

Susie Moore:

Gorgeous.

Steven Pressfield:

The book. Thanks so much, Suzy, by the way, seriously, for your great questions for being into this so enthusiastically. I really appreciate, it's great fun hanging out with you. Let's do it again. Sometime

Susie Moore:

I'll hold you to it. It I'll follow up. Steve, thank you so much. All the best of this incredible book, friends, all the links are included. Get your hands on this. Set yourself up for success. You deserve it. Your dreams matter. You matter. Steve, thank you. What a divine conversation. Thank, I'll just

Steven Pressfield:

Treasure this. Let's do it again.

Susie Moore:

Oh my gosh, I would love that. Best of luck to you, and I'll speak to you

Steven Pressfield:

Soon. And the same to you. Thank you, Susie.

Susie Moore:

Thank you, Steve.