All I’ve been seeing all over social media in recent months are Gabor Maté clips…

His latest bestselling book, The Myth of Normal, is breaking records all over the globe, and I can see why. I devoured it in several long reading sessions.

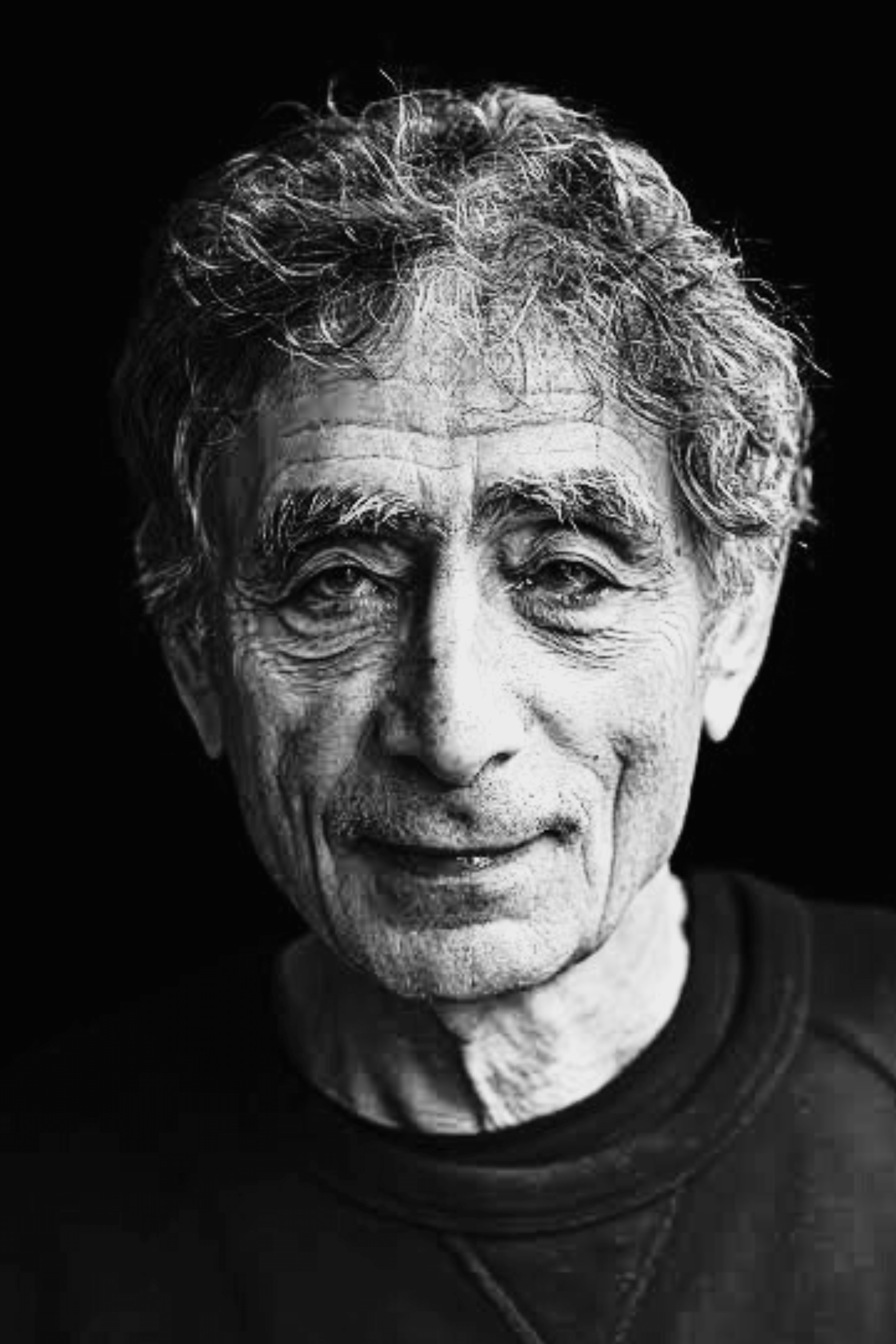

Gabor’s content is the only person I *never* scroll over when I see it. I stop. Turn up the volume. And give him my full attention. A renowned speaker, and bestselling author, Dr. Gabor Maté is highly sought after for his expertise on various topics, including addiction, stress, and childhood development.

This is NOT an interview to miss!

With love, 💕

Susie Xo

WHAT YOU WILL DISCOVER

Why we choose pleasing people over being real.

The cause of ADHD.

ADHD in adults, but ADHD in women in particular.

How being “too nice” can make you sick.

Why you should choose feeling guilty over feeling resentful – every time!

How anger is healthy.

The question to ask yourself, even if you had a “good, happy childhood.”

FEATURED ON THE Episode

Get my signature course Slay Your Year (Value: $997) for FREE if you leave a review of this podcast.

Podcast Transcript

Introduction:

Welcome to Let It Be Easy with Susie Moore.

Susie Moore:

My friend, having Dr. Gabor Maté on the podcast for me is a dream come true. Dr. Gabor Maté is, oh my gosh, I don't even know how to introduce this man. He is a highly sought after expert on a range of topics including addiction, stress, childhood development. His most recent book, The Myth of Normal, is trailing only behind Prince Harry in international book sales because he speaks about stress and trauma in the toxic culture that we live in. You've probably seen Dr. Gabor Maté all over social media because of this book and even in recent years, his explosive growth when he speaks about all sorts of things, health related and what their real causes are.

In this interview, we speak about a whole lot of things. We cover, choosing, being real over people, pleasing what that means to us while we are scared to do it, how being too nice can actually make you sick. This is all backed up by data. Why you should choose feeling guilty over feeling resentful. Ladies, I feel like this one is especially for us. We speak about healthy anger. We speak about what to do if you feel stress in your body, even if you've had a good happy childhood.

Dr. Gabor Maté is unmatched. He's unrivaled, unparalleled with the work that he does, the breakthroughs he brings to audiences who need him. And interestingly, we actually even filmed this podcast on a Sunday because he's very hard to book. This is a very, very, very busy man. And actually I start the interview by bringing up a trauma response that I had to him actually forgetting about our interview a couple of days prior. Hence, a scheduling on a Sunday. So my friends, this is a real, honest, real conversation and I'm thrilled to pass on to you now, Dr. Gabor Maté.

Dr. Gabor Maté, my gosh, what a privilege and joy to have you on the Let It Be Easy podcast. Welcome.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Oh, thanks for the welcome. Thanks for having me. It's a pleasure.

Susie Moore:

Now, before I hit record, Gabor and I are having a bit of a behind the scenes conversation. There was a bit of a mix-up as it happens often with scheduling, especially with such a busy person. And we were meant to do this interview a couple of days ago. I was ready and prepared and because of the mix-up, again, which happens all the time, nothing personal, Gabor didn't show up. I expressed almost like as a joke because so much of what we're talking about today is around Gabor's amazing book, The Myth of Normal: Trauma Responses as Adults.

I just said very openly, it's almost quite funny, I had this feeling, "Oh no, maybe my podcast isn't as special as some of the others if there was a scheduling issue with mine." Now, I'm conscious. I don't take things personally. I can bounce back from that. But I wanted to share it with you 'cause I thought it was kind of relevant and there's almost some humor attached to this. But when I shared it with you, could you share what you shared with me please?

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Yeah. I simply said that "My podcast is not important," it's not a feeling. We often say this, "I feel I'm not important. I feel I'm not important, or my podcast is not important." It's not a feeling. Feelings are I'm tired, I'm hungry, I'm sad, I'm angry. That I am not important, or my podcast is not important, I asked you, Susie, what is it? Then you said it's a story. Now, that story, it's a belief, it's a perception. The next question is, "What do you feel when you believe that you or your activities are not important?" What's the feeling?

Susie Moore:

Oh, it feels painful. It feels-

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Pain. It's sad. That's the feeling. And given that, as you pointed out, the scheduling mishap was completely...

Susie Moore:

Innocent.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

It's only innocent and had to do with the fact that I was traveling. Where does the story come from? And when somebody says something like that to me, "I feel such..." I'm saying, "You just told me about your childhood." And then I ask people, "When was the first time it occurred to you or it seemed to you that somehow your story, your existence, your contribution, you were not important?" And almost inevitably, not almost inevitably, inevitably you're talking about your childhood.

Now, I don't know anything about your childhood, but if I asked you how far does the sense go back that I don't matter that much, what would you say to me?

Susie Moore:

Well, I grew up with a lot of chaos. My dad was an addict, he died of addiction. We lived in domestic violence shelters. My mom was depressed. She had a lot of kids on her own. So being the youngest of five girls, I understand that her position was hard. But certainly feeling overlooked or feeling not having the attention that I wanted and needed, I know that that's ancient. And you say that all trauma is pre-verbal. I cannot tell you how much I've gotten from this book, how much I've learned from you, the work, your interviews.

So I mean it's so enlightening. I know that it's ancient. And you too, the way that you start this book with your airport story, for context, I love this because I so related to it too. Almost, not in an identical way, but similarly. So you're coming home from this speaking arrangement with this post speaking glow and you say, you are in your 70s. Your wife forgets to pick you up and then you are sulking for a couple of days like that.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

That's how our early imprints show up. The early traumas, the trauma symptom means wound, early wounds show up decades, decades later. So that when I get upset 'cause my wife didn't become up at the airport or didn't come on time to pick me up, and I make it mean that I'm being abandoned and rejected and all this. It's not what's happening. She's just late picking me up because she's an artist and she was painting in her studio.

In the same way, when I don't show up for your podcast and something in you makes it mean that I don't consider your podcast important, these are imprints of childhood. And then the emotions that arise, they're not caused by the present situation. They're triggered memories of what we felt as children and the stories that we had to tell ourselves. When your dad is addicted and you're going from shelters and your mother got her issues, you cannot help but conclude that you're not important. That's the conclusion you come to as a child. That's what you believe in. It's painful.

And those pains can show up decades later. And the whole idea is healing. And then I know your work is allowing in the joy, allowing in the vitality of life, my interest is what's blocking all that? And what's blocking all that is the stories that we developed in children that we couldn't help but develop as children in response to our experience. How do we drop those stories is the whole idea?

Susie Moore:

As I study your work, I think to myself, are we almost like all five-year-old children to some extent walking around in adult bodies? Especially when we have an overwhelming reaction to something, I remember one time my husband and I were skiing, I'm not very good and I fall over a lot, which is part of it. It's often quite funny. But in one moment I fell over and he said, "Come on, get up." I actually felt hurt in that moment physically, not dramatically, but I felt... And he was like, "Come on, get up." Not empathy. Not, "Darling, are you okay?"

I just cried and I was like that overwhelming response in that moment, I'm like, "This is not a 30-something-year-old woman who's fallen for the fourth time that day." So I'm like, "Are we just these children walking around with these responses?"

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Well, there's a spiritual teacher who I quote in the book and who I've followed for years and he said that there are very few adults walking around. In significant ways, we're children with the emotional responses of children. And this is always true when we get triggered. So we can actually walk along as adults and then something happens that reminds us unconsciously of some old dynamic and all of a sudden we become children. I've behaved like a two-year-old in the body of a 70-year-old. Actually, when people say to you, "Grow up already"?

Susie Moore:

Yes.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

There's kind of a truth to that. Or when they say, "Don't be such a baby."

Susie Moore:

Quite often.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

There are moments when we're all babies or children and now "grow up already" is not a particularly empathetic admonition. But if they said, "Do you realize that right now you're caught in the coils of some childhood dynamic," that would be very accurate.

Susie Moore:

Because you say that trauma limits response flexibility.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Yeah.

Susie Moore:

That's exactly what we're discussing here, right? It's like I almost cannot in that moment, not at least immediately. The initial reaction is, "Oh, this is no big deal. Oh, he's just saying get up, or oh, he's just got a scheduling something." The initial response is, "Oh, I don't matter."

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Well, so if you were present as an adult and your husband says get up maybe in an impatient kind of way or whatever, what would be a number of responses that you could give to that?

Susie Moore:

Well, I could just get up as I had been happily kind of laughing along.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

That's one response.

Susie Moore:

Yeah, I could say, I want you to speak differently when maybe you should check on me. You should ask us if I'm okay.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Exactly. You would say, "I'd love it if you're concerned about me right now rather than telling me what to do." Or you could say, "But when you respond with the pain, what happens is that the prefrontal cortex, this part of the cortex, the brain, which allows us to be flexible in our responses, they can choose between them. When we talk about freedom of choice, what real freedom of choice is, this part of our brain is functioning and we see all the choices in front of us and we make the decision as to which way we're going to go. That's what freedom actually is.

And what happens with trauma is it limits response flexibility so that we keep reacting rather than responding. And that reaction is not consciously considered. It's automatic and it's based on something very old. And then when people say, "I lost it, I totally lost it," what is it that they lost? They lost the prefrontal cortex. When we get triggered, it goes offline. And then we're just reacting like a much younger person being hurt by something. And this happens to all of us. But the important thing is to learn from it when it happens.

Susie Moore:

And this is really what your work is about. I mean, you speak of course so much about trauma and you explain, you make the distinction. It's not what happens to us. It's not any abuse we had or in a lot of cases it's not even what happened, it's what didn't happen, including good things. Maybe not happening to us. I love how you even describe in the book how people say, "Oh no, I had a good happy childhood." And then you ask them the question, "Who did you speak to when you were scared, sad, alone, worried?" And often we realize that we didn't actually speak to anybody.

There are so many things to learn in The Myth of Normal, but you explain that trauma is what happens inside of us, which is good news because it gives us much needed agency.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Well, exactly. Again, trauma means wound and the wound is what happens inside of us. It's not what happens to us, it's what happened inside of us. So trauma is not that somebody hit you in the head. Trauma is the concussion that you develop. Nope, somebody hit in the head is traumatic, but it's not the trauma. And you can wound children in two ways basically. One is by doing bad things to them that shouldn't have happened. It shouldn't happen ideally. An infant like me should be born into a situation where as the result of being Jewish, I could be killed as an infant. That's what happened to me.

It shouldn't happen to you that you're born to a father and a mother who are too caught up in their own traumas and their own dysfunctions to actually look after you do. And you have to witness all this pain and all this travail. So you can wound kids by doing bad things to them, but you can also wound kids by not meeting their needs. A lot of adults think that because no terrible things happened, they weren't abused, there wasn't a war, there wasn't a tsunami, there wasn't indicted parent, there was no violence in the family, nobody died. Therefore, they had normal happy childhoods.

And they don't realize that they still may have been wounded, not by the terrible things that happened 'cause they didn't. But by the good things that didn't happen, they didn't get the attention they needed. They me made to give the sense that they were important to their parents 'cause their parents were too caught up in their own stuff, as in your case. So you get the sense that you're not important. You weren't seen for who you were, you weren't listened to, your emotions weren't accepted and responded to.

And all that can really wound the child and can lead the child to develop negative beliefs about themselves. So often when somebody tells me, "I had an autoimmune... There's a physician, I can tell you for example that autoimmune disease happens mostly to women. 70 to 80% of people with autoimmune disease are women. And it has to do with emotional patterns, which we can talk about.

The commonest emotional pattern that people with autoimmune disease have is that they believe and they act as if their own needs weren't important and then to keep serving the needs of others. And they keep suppressing their own emotions to serve the needs of others. Well, those are based on beliefs and those beliefs happen in childhood. So often when somebody says, I had an autoimmune disease, I had an autoimmune disease, or I had an addiction, or I had depression, or I had anxiety, but I had a really happy childhood.

Then I issue what I called a happy childhood challenge. And I say, "Give three minutes," and let's find out how happy your childhood was. Inevitably, inevitably, they'll find that, yes, their parents loved them, their parents did their best. They had security of home and nourishment, and they went to a good school and they experienced pain that they hadn't considered 'cause then as you cite, when you ask them, "Do you ever feel upset, sad, alone as a child?" "Yeah." "Who would you speak to?" The answer is going to be nobody.

And that means that they felt alone as children, not because their parents didn't love them, because their parents didn't see them. And their parents didn't see them, not because they didn't want to, but because they were caught up in their own dynamics and because they hadn't been seen as children. So that question about the happy childhood usually breaks down very, very quickly. I've yet to see the exception.

Susie Moore:

I love to how you explain very clearly, you make it clear that parent blaming is inappropriate, inaccurate, and unscientific. You also say that it's cruel in the book. And you also say that you don't support unwarranted self-accusation.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Yeah.

Susie Moore:

Because we're so quick to go, "Oh, well my mother did this, or my father, or they were absent, or they were quick to say if there's an illness," because you speak so much about the mind body, which I'm excited to talk to you about. But we can then go, "I did this to myself. I've messed up my health." I mean, I want to just make that clear up front because I think that sometimes people think like there's shame attached to these conversations or that someone's done something really unkind or something bad. But this is just, it's

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Just reality. I'll tell you a story about blaming. My first book was on attention deficit disorder when I was diagnosed with it in my mid-50s. I never bought into the idea that it's a genetic brain disease. So I wrote my book and I explained that my own infancy under the Nazis, Jewish parents, my mother was really stressed and she could barely assure my physical survival. She certainly had very little time for my emotional needs given the terrible circumstances of living under the Nazis in Hungary in 1944.

I said in the book that I'm telling this story to indicate how... And my whole point is that when the mother is stressed, the baby is stressed and the baby deals with the stress by tuning out, it's a protective mechanism. And that mechanism we're tuning out gets programmed into the brain. So we're not dealing with a genetic disease here. We're dealing with the effect of the environment on the child's brain development. That's my whole point. Anyway, said in the book, right there in Scattered Minds, that's the title of the book, just been republished in the states this month, by the way.

And I say that I tell the story to indicate how the greatest love a mother may have, may not be enough to protect the children from her stresses. Now, the Toronto Star or Canadian newspaper reviewed the book and said, "Maté blames his mother." And I went to my mom, she was still alive and I said, "Hey mom, the Toronto Star says that you started the Second World War."

Susie Moore:

Oh my.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

And my mother said, "Sure, sure I did."

Susie Moore:

Wow.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Just people see blame and there isn't any. So it's a fine line. The fact is that the human personality and physiologically, the human brain, according to all the science, develop an interaction with the environment beginning in utero. And that also means that when mothers are stressed, those stresses get translated into physiological effects and psychological effects in the infant already in utero.

That's just reality. On the other hand, you're blaming the mother. No, you're not. Which mother chooses to be stressed? Did my mother choose the Second World War? Did your mother choose to be stressed or was she following the dynamics dictated by her own traumatic imprints as a child?

Susie Moore:

Yeah. My mom grew up in postwar Poland, 1942. It was nothing. It was horrible. Whatever we lived, I know that she had something far more extreme.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

On the one hand, we have to recognize. Now, me as a parent, I have three adult kids. I passed my trauma into them. I talk about this in the book, the meta normal. I passed my trauma to my kids. That's just how it is, through my workaholism, through my other addictive behaviors, through the significant stresses that my wife and I were faced with in our own relationship.

So kids grew up in an emotional war zone sometimes. Sometimes it was very playful and loving and light and delightful. But they never knew when the next storm was going to come and that affected their development. Now that's just the truth. That's how it was. Am I blaming myself? Well, I used to, but I don't because I didn't deliberately do it. I was acting out my own programming. So the thing is to recognize the truth without blame. You know what, I've often said to my kids, I'm not worried that you'll be angry with me, I'm worried that you won't be angry enough.

So I want them to feel their anger. But that's not the same as blaming 'cause blaming says you did something deliberately and knowingly. Anger says, "I don't like what you did."

Susie Moore:

And speaking of anger, you speak about anger in the book and how we've lost a lot of anger. I think women especially, and then we touched on this slightly, but how women who are very nice, "Nothing for me, don't worry about me." You even share a story about a lady when she was diagnosed with cancer. She's like, "Oh, what's my husband going to do?" That was her first question.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Well, here's what happened. This is an article in a Canadian newspaper. This woman is describing her experience, first person. Her name is Donna, I think. Her husband's name is Hai. And Hai's first wife died of breast cancer. And not Donna, the second wife is diagnosed with breast cancer. And the doctor says to her, "Don't worry, it was not like that of Hai's first wife. Her cancer spread had spread everywhere by the time they found it. In your case, it hasn't spread. You're not going to die." And Donna says, "But I'm worried about Hai. I'm afraid I won't have the strength to support him."

So here she is diagnosed with the condition. The doctor can't, in all honesty, tell her because we just don't know. But she's the one that regardless of the prognosis will have to have surgery, maybe radiation, maybe chemotherapy. And her first thought is, "But how will I support my husband?" Rather than, "Oh boy, what am I going to need here?" So this automatic regard for the emotional needs of others, suppressing your own is a characteristic of people that I've found and other research has found is present in many cases of malignancy and many cases of autoimmune disease.

We can talk about the mind body unity, how these traits actually affect the physiology. Now, another characteristic is that people who are very nice are often people who can't get in touch with the healthy anger.

Susie Moore:

Yes.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Now, healthy anger is, "You cross my boundaries, get out." That's healthy anger. It's in a moment. It's a healthy dynamic. Our brains are wired for it. It's a protection. It's a boundary defense. I'm not talking about rage and destructive acting out on others, I'm talking about healthy anger that says, "You're in my space. Get out." That's true emotionally or physically.

Or even if I may say, "When your husband says get up," you say, "Don't talk to me that way." That's just healthy anger. Now, who in this society is programmed by the culture to repress their healthy anger and to look after the emotional needs of others and always be nice? It's women.

Susie Moore:

Women.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

It's not biological, it's not gendered. It's not determined by biological gender. It's cultural. And that's why women have 80% of autoimmune disease. It also means that if you look at autoimmune disease or malignancy or whatever, if you deal with these emotional dynamics, your chances are much better. And that's been shown as well. There was a study out of Massachusetts maybe 20 years ago now, 15 years ago, they looked at 10,000 women... No, 2,000 women over a period of 10 years. And those women who are unhappily married and didn't express their emotions were four times as likely to die in that 10-year period than women who were also unhappy married, but did talk about their emotions.

So the issue wasn't happiness or unhappiness. The issue was did you express it or were you too nice? And did you repress it? That was the issue because that repression of emotions and anger actually has an impact on the immune system. It's women in this society who are programmed by the culture to take everybody else's needs and to suppress themselves.

Susie Moore:

Is that part of attachment? So when we speak about authenticity, when you speak about authenticity and attachment and how they compete, is that part of attachment?

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Well, yes. So here's the thing. Attachment, the way we are talking about right now means the drive to be close to somebody in order to be taken care of or in order to take care of. So there's a powerful attachment drive between infants and parents particularly, but not exclusively between infant and mother. Ideally, the child will have lots of other attachment figures. The father, the grandmother, the grandfather, your cousins, uncles, aunts. That's what we evolved as a species by the way.

We didn't involve in isolated nuclear families. So attachment is this drive for connection. Attachment is like a force of gravity. It pulls two bodies together. It's essential for survival, for birds, for all mammals, and certainly for human beings. I mean, if a child doesn't have an attachment drive or if the parent doesn't, what happens to the child? There's no survival. So that need is there.

It's with us all our lives. I mean, in order to procreate, we have to have an attachment instinct. In order to care for each other as adults, it's attachment, it's connection. It's powerful in human life. Now that's a need that we have, but we have another need as well, which is what you've named and is authenticity. Authenticity, alto the self being in touch with ourselves and being able to express who we are and to be able to stand in who we are.

Now, why is that important? Well, gut feelings, for example, that's being in connection with ourselves. That's being authentic is to know and be able to act on our gut feelings. Now, any creature in nature, how long do they live if they're not in touch with their gut feelings? Not very long. So we have this need to be authentic and we have need to attach. But what happens is, if you as a child, or I as a child or anybody as a child, gets the message that if you are in touch with your feelings and you express them, we don't like you, "We can't handle it. It's not acceptable."

You sit in a corner if you're angry and you sit by yourself. Or what message does the child get? The message the child gets is "Who I am is not acceptable. If I want to attach, I have to suppress who I am." It's not a conscious decision. We can't help it. It's an automatic survival mechanism because the attachment has to be maintained. And if I have to become less than myself and suppress myself in order to attach, to belong, to be accepted, I will do that.

But once we do it, we get out of contact with who we are and we spend the rest of our lives not authentic. We tend to comply, to accept other people's opinion about ourselves. We tend to want to fit in, to be accepted, to be nice, to conform, to belong. We do this in our relationships, in our marriages. We do this at work, and it's almost like we're living the life of somebody else until some crisis happens. A divorce, a relationship breakup or repeated ones or friendships that don't work, or a sense of alienation that would just, "I don't feel like I am who I am. Who am I anyway?"

Or some illness, depression, anxiety and addiction or an autoimmune disease or a flare up or frequent colds or headaches or migraines or frequent back pains or whatever. And then we say, "Well, what's going on here?" So something has to happen to wake us up and then we start saying, "Well, okay, how can I find out who I really am?" So that the joy and the happiness that is my birth is actually accessible to me. 'Cause right now it isn't.

Susie Moore:

This is where it gets a bit tricky too, because we are often rewarded for our attachment behavior, right?

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Yeah.

Susie Moore:

So being a compulsive over helper or being a work... Like you mentioned in the book, and even just now, alcoholism like that being a virtue, no one is going to stop you in America. If you are working in overdrive, they're going to go, "Good job." There's going to be praise credit. There's going to be rewards for that. So this is part of The Myth of Normal, the toxicity that we have and how we abandon ourselves. And there are prizes, medals, money for the things that can make us sick.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

And that's why the subtitle of the book is Trauma, Illness and Healing in a Toxic Culture. One of the toxicities of the culture is one of the poisonous aspects of our culture is it rewards behaviors that deny the self. So as a physician, as a workaholic physician, I got nothing but recognition, admiration, gratitude and more money. The fact that I was neglecting my kids emotionally, I wasn't available to them 'cause I was too busy out there being this physician.

The fact that my marriage suffered because emotionally I wasn't available. The world didn't see tha.t I just got rewarded for this behavior. Now, why was I workaholic doctor? Because the sense I got as a kid was just like the sense you got as a kid that I wasn't important. Now, if you don't think you're important, well, ways to deal with it just to go to medical school. I know you'll be important. And they're going to want you all the time at the risk of further losing yourself and of impoverishing your emotional life and your relationship life.

So the world rewards us for the wrong things. And so you see this all over the place, that some of the most successful people are also some of the most miserable ones. There's this success that defined by this culture is how much money you make, how much you achieve, how much you own, and how well you look. None of that has to do with the real self, none of it. And the more you're craving that kind of attention. So here's the thing. Say physical attractiveness, which is very much... I mean, it's important to both, all genders, but it's particularly a demand on women.

Now, if you didn't get the attention that you needed as a child just for who you were, and every child deserves attention, not 'cause they're pretty or smart or good, or compliant, or nice, or successful at sports or cute just 'cause they are. But if you don't get the attention... This is just a need of the child. It's a nature determined developmental need of the child.

Now, if the child doesn't get the attention they require just for who they are, then they'll be consumed with attracting attention. Now they want to be attractive. And the result is the fear of aging, especially for women, but also for men. The multi-billion dollar cosmetic surgery industry and all these products that are designed to improve your appearance without ever satisfying your need for real attention. 'Cause if they pay attention to me because I'm smart or helpful, that part of me that never got attention just for who I was, still is hungry. And if they pay attention to you because you're good looking or because you're helpful or because you're clever, that part of you that never got the attention, but it needed just for existing just because you're human being, it still remains hungry.

And then we go on Facebook and we present this face to the world, and then people like us, but they don't like us. They don't even know us. They like the image that we presented and then we have friends. No, we don't. Those friends don't know who we are. Millions of people are caught up in projecting an image. And you have all these influencers that are all about image and not about the real self. That's the toxicity of our culture, one of the many toxicities of this culture.

Susie Moore:

I sent an excerpt of your book to a friend of mine who is... Or she was an influencer. She's packed it up and I think she's exhausted. She's on a long-term break and the passage was about how a loving parent can let you be spectacularly ordinary. That really stood out to her and she was like, "Wow, it would be a sin for me to be ordinary." I get it. There's a specialness that's encouraged, right? It's like, "Are you really quick? Are you the cutest? Are you the most insightful, the most wise? Are you the most woke?"

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Well, here's the thing. We're all special.

Susie Moore:

Yes.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

But the specialness is our uniqueness. We don't have to add to it. We don't have to prove it. If you have to work to prove it, we are going outside ourselves now and we are defining ourselves according to other people's expectations. So you get some of these great stars who are just so supremely talented and charismatic. They got this adulation and they end up dying in the bathtub or in a toilet seat like Elvis or drowning in a pool, or overdosing, or killing themselves. But none of that "specialness" had to do with their real self.

Susie Moore:

And this is where we lose our agency, right? Because you share in the book the four A's when it comes to healing. And oh my gosh, what you say here, I was like, "If you could see how many underlines I've put through it, truly... It's page 378. If you remember what you say around the four A's of healing. You can see how I've highlighted and circled everything here. May I read a paragraph?

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Well, please. Of course, yeah.

Susie Moore:

I know that a lot of our listeners, they create things. They have their own businesses, their own blogs, social media, all those things that are neutral. They can be healthy and fun and they can bring a lot of blessings, but what I love here, when you speak about agencies specifically around healing is agency does mean having some choice around who and how we be in life. What parts of ourselves we identify with and act from. This often starts with the renegotiating our relationship with a personality traits. We have so long taken to be identical with who we really are, the ones that arose in us to keep us safe, but now keep us boxed in. There is no freedom in having to be good or the most talented or accomplished, or in the need to please or entertain anyone or be interesting.

It's like, "Well, that's your job. You've got to be talented. You've got to be the best. You got to be number one. Got to stay number one, once you're there, then there's a pressure of just the maintenance of that spot. And then where can we go farther? Ambition is rewarded and seeking... How do you almost identify the difference between natural healthy ambition to create and to contribute, and then the, "Oh, I have to be entertaining and interesting."

Dr. Gabor Maté:

So the desire to have meaning and purpose in one's life, to express someone's creativity, to develop one's talents, to make a contribution. Those are just healthy, normal human desires. They go along with being a human being. But to do all that in order to be accepted by others is a totally different kettle of fish. So amongst children have four basic needs. The first one we already talked about, emotional needs, I mean needs for healthy development.

We already talked about the first one attachment, the strong attachment relationship. We should feel absolutely secure. Now the second need is that inside that attachment relationship with the parents, the child should not have to work to make the relationship work. The child should be able to rest from the work of having to make the relationship work. They shouldn't have to be any of those things. The relationship should be just there unconditionally. So when people are driven to... Let me come back to my favorite example again, myself. Everybody's-

Susie Moore:

I love your examples the most.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Everybody's favorite example is themselves. So as a physician, the desire to help humanity and to promote healing, that's a genuine, authentic desire of mine.

Susie Moore:

Yes.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

It always has me. To use that in order to be respected and to be needed, and wanted, and valued, that has to do with my childhood need. I didn't have any rest because that desire can be there, and then I just be serving that natural impulse towards self-expression and meaning and purpose in life. Whatever that is for you, that's great. But if it's polluted with this need to impress others or to dominate others, or to get them to like you, then your natural sense of purpose and meaning gets distorted in the service of something else. And to that extent, it will not satisfy. So that's the fine line between... Susie, I just lost your picture.

Susie Moore:

Oh, you sound good to me.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Okay, good. I can hear you. I just can't see you at the moment. Okay, that's fine.

Susie Moore:

I can see and hear you great.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Okay. Well, as long as you can see yourself, that's good. In fact, the whole idea of this whole conversation is to help people see themselves, isn't it?

Susie Moore:

Exactly. Let's leave this in. Yeah.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Okay. What was I talking about?

Susie Moore:

You're saying that the desire to contribute is sincere and beautiful and natural, but it's when we want to be better than others or when we want to maintain a certain spot or do it for adulation, that's where the line is.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Exactly. I was going to say something else, but I've forgotten so I'll let it go for now.

Susie Moore:

It'll come back.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Maybe it'll come back or it won't.

Susie Moore:

Yeah. One thing that I love that you say about authenticity is because it's not a tangible thing. We can't measure it. It's not visible. But what I love, the question that you ask in the book is just to notice when it's not there.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Yeah.

Susie Moore:

Because that we feel. It feels like a hollowness or a fake smile or something.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

That's right. Haven't we all had the experience of being in a conversation with somebody? And then afterwards, I wasn't being honest there. I wasn't being authentic there. I was agreeing in order to be liked. I wasn't saying how it was for me because I was afraid I would be rejected, or I was just trying to fit in. As you say, there's a hollow feeling about it. T.

He thing is to notice that without being critical of oneself. I used to feel shame around that when I would do that in the past. I remember that shame. The thing is to be curious about it. Wonder why I did that? Wonder what made me do that? What was my fear of being myself? And the important thing about noticing it is not just to notice it so that we don't do it again, but there's something deeper here. When you're noticing, who's noticing?

Who's noticing? Who's noticing that I'm not being authentic? It's the authentic self that's noticing it. So then noticing it, automatically strengthens the authentic self. And of course, we all do it. Every time we do it, if we notice it afterwards and can sort of just ask ourselves, what was my fear? Or what was my belief? That strengthens the authentic itself. And that's why actually a lot of us, as we get older, we actually get a lot fear. I've known a lot of women who are on menopause or afterwards.

All of a sudden they experience the freedom because they don't give a damn anymore. They'd much rather be themselves than be accepted or at the cost of suppressing themselves. Well, the fact is we don't have to wait till old age.

Susie Moore:

I love that. I love observing that freedom that you see in people sometimes when it's just like, "Nope." And you actually have a great passage in the book too. It's on page 142, the chapter before the body says no. And there are six questions that you ask, and it actually is about the word no and how scary it is for us to use sometimes and questions to play with. Again, this is such a curious exercise. There's no judgment around it. You're just, "Huh? Where did I say no to? Where did I want to say no today, but I didn't? What was my story? What would I believe about myself if I said no in that situation?" Could you speak to No for a moment? Because I think it's scary. I think especially for women maybe. I don't know. Men too, but yeah, the "no" thing is hard.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Well, so an earlier book of mine is called When the Body Says No. And it's about the mind body unity about how... This is just the science of it. This is not clever intuition. This is science. I also noticed it. But the science is there that, again, the people that tend to develop chronic illness tend to people that don't know how to say no to the emotional needs of others. Do you have children, by the way?

Susie Moore:

No, I don't.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

No. All right. Well, if you did, you'd find out that was the first thing a kid says when they get to be year and a half.

Susie Moore:

Oh, I used to be a nanny and I know the power of no in children. It is fun. And they are resolute, yeah.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Yeah. Why don't they start saying yes first? Wouldn't it be nicer for us. Time for dinner?

Susie Moore:

Yes.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Yes. Time to put-

Susie Moore:

Time for bath. Yes.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Time for bath. Yes. No, they say no. Now, why did they do that? They do that 'cause nature's very smart. And nature says that if you don't know how to say no, your yeses don't mean a thing. So in order to develop your own will and your own sense of what you value and meaning, and who you are and what you like, what you don't like, you have to be able to say no.

At first, it's kind of automatic, and then that automatic little no, that the kid utters is a little wall behind which their own will can develop. Okay. Then what happens is a lot of people don't know how to say no anymore. There's a no there they want to say, that wants to be said, but they don't say it. Now, what I noticed in family practice is that when people don't know how to say no, their bodies will say it in the form of illness.

So that chronic illness is very often the body saying no when the person couldn't. And if the person develops the capacity to say no, their potential to heal is much better. Now, where does this come from? Given that nature gave us that no, as a birthright, how did we lose it? We lost it because we learned that in order to be accepted and attached to, we had to please others.

So the saying no becomes a very scary proposition. So you told me you lived in Miami. Let's say I landed in Miami next week and I called you up and, "Hey Susie, should we go for coffee?" But you've been up all night because your husband was sick, and you were tired, and you didn't say no. The exercise says, "Where this week did you not say no?" It doesn't know that wanted to be said. Okay? Then the second question is, "What was the impact of you not saying no?" So if you had been up all night and I asked to go for coffee and you said no, what would be the impact on you, do you think? How would that affect you?

Susie Moore:

We are getting into my next favorite question, which is around resentment and how that feels in the body, and feeling stretched, feeling annoyed with myself.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

So you'd feel resentment and physically what would happen to you? You just hang up all night.

Susie Moore:

Yeah. Your body says a physical no somehow.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Yeah. Well, you'd be tired for one thing. And then the third question. So the first question is, "Where did I not say no? Where is that no that wanted to be said? "And that happens in two areas, work and personal relationships. So your partner wants to have sex, but you don't feel like it. And you don't say no. That's an example. Or a friend wants to go for coffee, or your boss wants you to take on another project and you don't say no. What's the impact? The impact is going to be tired and all kinds of other things, and you'll be resentful.

Susie Moore:

Yeah.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Then the third question is, "What's the belief behind me not saying no?" So let's say I do come to Miami and I do ask you for coffee, and you have been up all night and you don't say no. What would you believe? What do you think would be your belief that would have you not say no? What would you be believing? If I say no, then what?

Susie Moore:

If I say no, then, well, I'm not in a position to, because I'm not special enough to say no yet. I have to earn affect. I have to work at things like my needs aren't worth much.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

I don't have the right to say no. I don't have the right to say no. Or if I say no, he won't like me. Or if I say no, I'm being-

Susie Moore:

Yeah, and that's it.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Or if I say no, I'm being self-

Susie Moore:

There's a risk.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Yeah. There's always some story. Anyway, so the exercise takes people... Now, I've been told by many people that just doing that exercise regularly has totally changed their lives.

Susie Moore:

When I brought this word up, resentment, one of my favorite things I've ever heard anyone say ever was from you. And it was about resentment versus guilt. Do you remember this?

Dr. Gabor Maté:

I do.

Susie Moore:

I've told 7,000 people about this already, and everyone is like, "Whoa, really? I get to choose?" Would you share with that?

Dr. Gabor Maté:

I wish I could claim authorship, but I didn't. I can't. I heard it from a therapist, and they said, whenever there's a choice with resentment and guilt, choose the guilt every time. So if I show up in Miami and I would, "Let's go for coffee," and you say no, and you feel guilty, that's better than you say yes and you feel resentment because the resentment really is the poison. And it really does eat you up. When you think of when you're resentful, what does it feel like inside to be resentful?

Susie Moore:

It's horrible. It's like this seed that grow and it makes you mad with everyone. Yeah. I mean, I even had a friend recently down here in Miami. She was attending a wedding she didn't want to go to, but she was like, "Oh, I should go because it's the right thing." And then of course there's money time. There's also a travel delay. The whole thing just made her... And I was like, "If you do this over a prolonged period, it's going to impact your health." All of this, yes, yes, yes.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Yeah. So I say choose the guilt because the thing with the guilt, it's one of these dynamics that I call jokingly the stupid friend. And what I mean by that is that guilt came along in childhood. When you said no to people, the guilt came along to keep you saying yes. Because to say no threatened your relationships. So the guilt calling says, "You better say yes, and that'll keep you in your attachment relationship." So it's a friend that wanted to keep you safe. The stability comes in that the guilt hasn't learned that you're no longer a four-year-old, that you're actually free now to make your own decisions without having to comply.

But the guilt doesn't get that. So I just say, "Treat it like a stupid friend." "Okay, here you are again. Thanks, but no thanks." So choose the guilt and once you do, you'll find it'll start learning that it's okay for you to choose yourself. So choose the guilt.

Susie Moore:

Because just through the...

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Go ahead.

Susie Moore:

So through the act of choosing guilt again and again, it almost like the volume of it becomes a new normal. Almost unhealthy.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

It finally gets it that you can handle yourself and it doesn't need you anymore. There's healthy guilt, of course. If I showed up on this podcast inebriated. I mean, I don't drink. There's no chance of that. But if I did, I should feel some healthy remorse. But that's not what I'm talking about.

Susie Moore:

Right.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

I'm talking about that sort of cause of guilt that [inaudible 00:57:24] from being yourself.

Susie Moore:

Yeah. One thing that comes up in my community quite a bit, Gabor is I work with a lot of women who are determined. Have you heard this, the sandwich generation?

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Yeah.

Susie Moore:

So taking care of kids and aging parents, and they have a lot of guilt around their parents like, "Should they be living with me?" You even shared the story in the book too about one man who was having two dinners a night because he didn't want to not have dinner with his parents. I just feel like it's so pervasive and it can feel very real, the guilt.

What advice would you have for someone who's like, "Gosh, I'm not there 24/7 for my aging parents. Plus, I've got a job. Plus, maybe even a single mom."

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Well, first of all, it's part of the sad realities of our culture is that caregiving is no longer communal. Because, again, we grew up in small communal groups where caring for the vulnerable wasn't the task of one particular person, it was the communally shared task. During COVID, there's a chapter title in the book called Society Shock Absorbers, which is about women. And the title comes from a New York Times article that came out during COVID where women took on the task of absorbing the stresses of their spouses and their families, and they felt guilty when they couldn't liberate their families from stress. They felt guilty because they assumed that it was their job to do that.

Now, the sandwich generation, again, partly it has to do with how poor we take care of the elderly in this culture. In fact, even the word, elderly, indigenous people don't talk about elderly. You know who they talk about? They talk about their elders.

There's such a difference between the elders and the elderly. The elder people these days keep calling me an elder and I still kind of, "Pardon me, what are you talking about? I'm only 79." But the elder is a respect as somebody who's part of the community. The elderly is just a burden. So part of it has to do with how we look at aging, which is, again, through a very materialistic. Can you still produce and consume? If not, you're kind of useless.

And that job of looking after, typically, because the caregiving role in this society is culturally determined to fall on women. Women do find themselves in the center of situation. It's very stressful. It's very stressful. I don't know how to resolve it for people except to say you have small children and any caregiving that you... And by the way, we haven't talked about this, but this often happens to be men and women particularly in our culture is that the woman becomes the caregiver to the husband as well.

Susie Moore:

Yes.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

The emotional caregiver. My wife took on that role and she suffered as a result. The depression that she suffered wasn't some disease that she had, it had to do with being overstressed, looking after the emotional needs of an adult child and small children. And we figured that out. We've learned it, but it took some time. What I see in women is you're going to have to make a decision, which child would you rather look after? The small one or the adult one? Because any energy you put into look after the adult child is taken away from the little ones. Just as how it works.

Now, when it comes to aging parents, it gets a bit more dicey because you want to honor your parents and you want to look after them. But still, you have to decide how much energy do you have and how much time do you have? And that caring energy that you have, how many ways can you split it and where would you rather put it? At least ask yourself these questions.

The problem is people don't even get to ask those questions. They just fall into that role automatically, and they automatically become the shock absorbers for everybody else.

Susie Moore:

If you could go back to you, say, maybe a 40-year-old you who is working all the time, young children... I mean your wife, I love how her art is in the book, and she sounds very wise, I have to say. What would you tell yourself? If you could sit yourself down for a moment and go, I've got some news from for you from 70 something me, what would you...

Dr. Gabor Maté:

What would I say to myself? I'd say that your unhappiness is not necessary. Your unhappiness and drivenness is based on dynamics within yourself that you can discover and gain agency over. They don't have to ruin your life. You can be free. And that freedom is your right and your need. It's your responsibility and your possibility to attain that freedom. That's what I would say.

Susie Moore:

I think this is a message for all of us. I mean, the message of the book, this is not a gloomy book, this is a book of optimism. I mean, I even love how you end the book. You say that we're blessed with a momentous opportunity right now with so much data coming to life.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Yeah. I think, the possibility of transformation, the possibility of growing up, the possibility of liberation exists in this present moment. That's the opportunity. I wouldn't have written a book if I wanted to deliver bad news. And you know what? I can tell you, there's a song by Bob Dylan where he sings, almost so much older then. I'm younger than that now. That's actually possible. Younger, not in the sense of being more immature and childish, but in the sense of being more liberated than childlike.

Because, again, to go back to your joy and your vitality, I mean, you see them kids all the time. And then we get older and grimmer, and glamour, we can be younger again. We can be freer, we can be more joyful if we deal with the self-erected bars that keep us in prison. Self-erected, not in the sense of guilt or blame, but in the sense that these are the dynamics we develop to survive our childhoods, and now they keep us burdened and we can liberate ourselves from it.

Susie Moore:

So Dr. Gabor Maté, what's next for you? What can we look out for? Everyone needs the book, The Myth of Normal. This is a must read. I wish this were a staple in every home. I think it is already in millions of homes. But I mean, what's next for you? What can we look forward to with you? Anything we can join? Anything we can have more access to?

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Well, I'm happy to say that wherever the book has been published so far, it's done really well. Today as we speak, it's 10th week on the New York Times bestseller list. In Canada, it's been the number one or number two bestselling nonfiction books since it was published in September. Today, it's taking second place to Harry. So everybody's wild about Harry these days. But that's okay.

I'll take that. In Hungary in my birth country, it's been a number one nonfiction book for last four months. So it's doing very well. What's next for me is my son and I with whom I wrote this book are writing another book together.

Susie Moore:

Daniel?

Dr. Gabor Maté:

It's called Hello Again: A Fresh Start for Adult Children and Their Parents. Because we've had such stress and strain in our relationship. We've had to work a lot of... It's based on a workshop that we do. It's called Hello Again, and that's going to be our next book published 2024. I travel a lot. I speak a lot. I mean, speaking of saying no, even now it's like I just got an invite to do something today, and I have to say, "No, I can't do it this year. This year is already full up."

So what's for me is all kinds of interesting projects. People want to do TV series and this and that and the other. But what's next for me, in addition to the work that's out there, which is all very exciting, is going deeper into my authenticity and deepening my relationship with my spouse, and being more present in my life. That's what's really next for me.

Susie Moore:

So this never ends. There's never a point of arrival. It's not like, "Done the work. I'm good. I'm authentic, I'm clean."

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Yeah. I've said this a few times, maybe you haven't heard it, but I've written my own epitaph. It's going to be engraved on my gravestone. Have you ever heard that line of mine?

Susie Moore:

No, not yet.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

All right. On my gravestone, it's going to say, "It was a lot more work than I had anticipated."

Susie Moore:

How real, so real.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

'Cause it's ongoing. It's ongoing.

Susie Moore:

I mean, think about it. On the brink of 80, you are busy. Booking you, I mean I can tell it from someone on this side of it like you are a busy, busy human being. Traveling. You are packed. We're doing this interview, friends on a Sunday. Your commitment to your work, to this message, I mean, it must be wonderful to just be so full of things to do and people to connect with and to help heal. Are you enjoying this period, personally?

Dr. Gabor Maté:

It's a beautiful ride. I did overdo it on the book tour. I traveled for three months and I was barely home and I got depleted emotionally. My relationship with my wife suffered as a result. But now we've taken the time to take care of it. It's all good. So it's a beautiful ride as long as I know how to say no.

Susie Moore:

Oh, message for us all. I mean, truly, I could keep you forever. I hope you get to connect again in the future. Truly, I really do. I love your work. I appreciate so much what you do. You've helped me so much. I share your messages far and wide. And everyone, The Myth of Normal a must purchase if it's not already in your home. Dr. Gabor Maté, what an honor, what a joy. Truly, this has meant so much to me. Thank you so much-

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Well, I really-

Susie Moore:

... for being in Let It Be Easy podcast.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

Thank you. I really enjoyed your very carefully thought out questions and the energy that you brought to it and just the opportunity to speak to the audience. I'd just like to mention one resource of mine, which is a film.

Susie Moore:

Please.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

It's a film that's available online. You can watch it for free. The filmmakers are raising money to make their next film, so you can make a donation or not, but you could put zero $00 in, but it's called The Wisdom of Trauma. So you go to www.wisdomoftrauma.com and that's a film that's been seen by about eight to 10 million people internationally now. It's on my work on trauma. It's not light watching, but a lot of people find very meaningful. It's a film that many people listening may want to take in.

Susie Moore:

www.wisdomoftrauma.com.

Dr. Gabor Maté:

That's correct. Yeah.

Susie Moore:

Beautiful. Thank you. Thank you. A thousand thanks, Dr. Gabor Maté. And until next time, my friends love and eat.

Hey friend, I've got something really cool for you. I want to give you free access to my signature course called Slay Your Year, which typically sells for $997. You can check it out, all the details at slayyouryear.com. All you have to do to get access is leave me a review. Leave a review of this podcast on Apple Podcasts. Take a snapshot of it and send it to info@susie-moore.com. That's info@susie-moore.com and we'll get you set up with access.